Why and how did Tallinn’s cathedral obtain a new retable for itself in 1696?

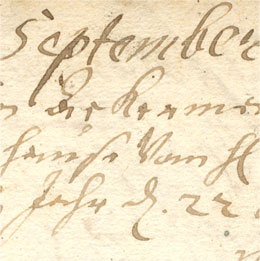

A great fire broke out throughout Toompea on 6 June 1684, and most of the furnishings of the cathedral were destroyed. King Charles XI contributed to the restoration of the cathedral by announcing a collection to restore Estland’s most important church, which was under his care. The province’s Governor General Axel Julius de la Gardie was the local official responsible for the preparation of the retable, and he concluded the necessary employment contracts with the wood carver Christian Ackermann, the joiner Hermen Berents, and the portrait painter of the Knighthood of Estland Ernst Wilhelm Londicer.

What place do the figures of the cathedral’s retable occupy in Ackermann’s oeuvre and the history of Estonian sculpture?

Carving the figures of the cathedral’s retable was the culmination of Christian Ackermann’s career. These sculptures also came to be considered masterpieces of the art of wood carving in the Estonian baroque era. Good proportions characterise the cathedral’s altar sculptures, taking into account their position high up and far from viewers. Compared to his predecessors, Ackermann had a remarkably good knowledge of anatomy. Ackermann’s carving technique and the quality of his use of material are also notable. These are manifested in the personalised and finely detailed treatment of the figures, for instance, and in the use of linden wood blocks, which are glued together and reinforced using forged nails.

Which figures can the sculptures of the cathedral’s retable be compared to?

The sculpture of the Apostles Paul and Peter on the main level of the cathedral’s retable can be compared with Ackermann’s earlier retables in the churches at Simuna (1684) and Vigala (latter half of the 1680s), as well as with the sculpture of Paul and Peter standing at the stair portal of the cathedral’s pulpit (1686). The comparison indicates how the apostles depicted by the master wood carver aged together with him.

The sculptures of the evangelists sitting on the cornice of the retable’s main level are unique in the context of Ackermann’s oeuvre: figures of the evangelists are not found in any other retable, much less in a sitting position. They generally stand on the corpus of pulpits beside the beatific Christ, the figure known as Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World). The sculpture of Mary Magdalene on the retable’s cornice is also exceptional in the context of Ackermann’s oeuvre and of Estonian baroque retables more broadly, and there is nothing to compare it to. At the same time, the figure of the angel in the cathedral’s retable can be compared to the cornice figures of Ackermann’s retables in the churches at Türi and Martna, as well as with those on the sounding board of the pulpit of the church at Karuse. The statue of Christ the Invincible can be compared to the topmost figure of the Martna retable, the artistic level of which is inferior to the quality of the cathedral’s figure.

How did the polychromy of the figures of Ackermann’s cathedral retable support the figures?

Polychromy – colour, including gold and silver – played an important role in the art of wood carving in the baroque era (as it did in earlier styles). The more that sculptures carved out of wood resembled living people and expressed emotions and the more brightly coloured and resplendent they were, the greater their effect on viewers.

What is extraordinary about Ackermann’s carved cathedral retable figures is the complete gilding of their garments, which gives an indication of the importance of the work and of the customer’s fat purse. The finishing of the faces of the figures carved like portraits is also noteworthy: the smile painted on the face of John the Evangelist, and his gaze directed towards the heavenly heights through the use of colour are indicative of the awareness of the painter, Ernst Wilhelm Londicer, of the possibilities for the art of painting to “work wonders”.

What was the original retable of Tallinn’s cathedral like?

The retable of Ackermann’s time differed significantly from the retable that can currently be seen, which underwent a thorough reconstruction and redesign in 1866.

The retable was originally lower by one or two socle storeys and thus its proportions were altogether different. Instead of one large central painting, it displayed the picture Püha õhtusöömaaeg (The Last Supper) and/or Kristus ristil (Christ on the Cross), painted by Londicer. The employment contract concluded with Londicer indicates, and paint analyses verify, that the architectonic parts of the retable were coated with black lacquer, the bodies of the figures were flesh tone, their clothing was gilded, and the golden initials of King Charles XI were on a blue background (see the reconstruction).

In the opinion of the art historian Sten Karling, the cathedral’s retable was made according to plans drawn up by Sweden’s royal architects, Nicodemus Tessin the Elder and the Younger. In terms of architectonics and a few decorative details, the retable of Stockholm’s Riddarsholm Church resembles the retable of Tallinn’s cathedral, with its Italian-style language of form, created according to the design plan of Nicodemus Tessin the Elder.

What is the message of the retable?

In the context of Estland, the iconography of the retable, which should be read starting from the bottom and moving upwards, is abundant: the painting Püha õhtusöömaaeg, which was on the altar’s central axis, spoke of the betrayal of Christ, treachery and the weakness of human nature. The painting that followed this, Kristuse ristilöömine (The Crucifixion of Christ), spoke of the redemption of mankind and the divine blood sacrifice. Crowning the retable is the figure of Christ the Invincible, bearing a golden flag of victory and treading on the serpent and the skull of Adam, symbolising the victory of Christian life over death and sin.

The two most important of the twelve apostles for Lutherans stand on the main level of the altar: the apostle Paul, holding the Holy Scriptures and a sword, and the apostle Peter, holding the Holy Scriptures and the key to heaven. The four evangelists sit with their books and attributes on the cornice of the retable: Mark with a lion, Luke with a bull, Matthew with an angel, and John with an eagle.

Mary Magdalene and an angel are beside Christ at the very top of the retable as references to asking for and receiving forgiveness, and the hope of eternal life.

What might have happened to the retable after the Great Northern War?

Russia declared war on Sweden in 1700. Ten years later, Russian forces laid siege to Tallinn. Since a plague epidemic had broken out in the city, the troops in the city were incapable of defending it, and Tallinn capitulated.

It is impossible to say exactly what happened in Tallinn after the city capitulated due to the scarcity of sources. At the same time, references have been found indicating that looting took place in the city that was already devastated by war and the plague.

The furnishings of Tallinn’s Cathedral were altered in the 1720s after the end of the war. There is no known information indicating that the church was looted or that it had suffered damage in some other way during the war. It can instead be presumed that the new ruler wished to bring the region’s cathedral into harmony with his rule. The initials of King Charles XI of Sweden were replaced by the letters α and Ω, denoting the beginning and end of everything. The retable’s architectural part, which was originally coloured black and gold, was coated with light tones suitable for the rococo period, and spots on Ackermann’s figures where the paint had been damaged were retouched. Additionally, Gloria, a golden sun bearing the name of God in Hebrew, was mounted on the retable, and the curved canopy was also redesigned – with its tufts, the wavy arch of the curved canopy that has hitherto been ascribed to Ackermann is secondary. In light of new archival discoveries, the sculptor Salomon Zeltrecht, who worked at the same time in Kadriorg, may have been connected to the retable’s redesign. The new Archpastor Christoph Friedrich Mickwitz took office in 1724. The wish was to fix up the entire church in honour of his arrival. As part of this work, Tallinn’s Cathedral was given a light overall colouring.

What happened in 1866?

In the 1860s, the high point of nationalist awakening among Baltic Germans and of confessional Lutheranism prevailed in Estland, and the cathedral’s retable – the Pantheon of the Knighthood of Estland – was updated.

Otto Pius Hippius, who was the first academic architect in Estland and worked primarily in St. Petersburg, drew the project for redesigning the retable. He was assisted by the Tallinn artist of German background Theodor Albert Sprengel.

In order to replace the two old altar paintings with one large painting, the retable had to be made two levels taller. This also altered the retable’s proportions. The altar became considerably more vertical and monumental. At the same time, the typically baroque multicoloured figures of Ackermann and Londicer were painted white in order to give the wooden sculptures a more noble appearance by making them look like marble sculptures. The redesign of the retable, the widening of the altar table, adding to the height of the retable, painting and gilding, and the purchase of a new altar painting cost a total of at least 2,416 roubles. The church’s account book indicates that the altar painting alone cost 1,000 roubles.

Eduard von Gebhardt, a Baltic German artist who had studied in Düsseldorf, painted the cathedral’s new altar painting Kolgata (Calvary). The cathedral’s altar picture is exceptional in the history of Estonian ecclesiastical art since for the first time it depicted Christ’s mother, the Virgin Mary, as an old woman commiserating with her son’s sufferings. In the picture, Christ has also not yet turned away from worldly life; rather, he fulfils his last earthly duty: he asks his favourite disciple, John the Younger, to look after his mother. Prior to being mounted over the altar, the painting was put on display at the Estland Provincial Museum, where it earned the approval of the public, but was also subjected to scorn for what was considered to be its excessive realism, as is verified by the newspaper.